Inaugural Edition

![]()

Opening

Lines of

Communication

with LGBTQ

Youth

A Re-do on

Civil Rights

Thanks to

Black Lives

Matter

Why Critical

Race Theory

Matters

Gloss of Larsen-

Freeman's

Complexity

Theory

Self-

Determination

in Individual

Plans of Study

Questions on

Nuclear Power

from the Pre-

Fukushima Era

Thought

Experiment

to Learn

Action Research

SEE WINTER

EDITION FROM

Nov 2020

to Mar 2021

editor@

Information:

multilingual

adaptive.net

![]()

A Warrior Ethos Applied to the Kansans CAN Initiative

Incorporating Self-Determination in Individual Plans of Study

Abstract: The decision in 2014 by the Kansas State Board of Education to require individual plans of study (IPS) for eighth through twelfth graders came 24 years after a transition planning mandate appeared for the first time in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 1990). It is argued by the author of this paper that the roll-out of “Kansans CAN” and the IPS in schools across the state, now in its fourth year, would benefit from incorporating more of the best practices which have been developed by special education professionals and transition IEP teams over the past several decades. In particular, it is suggested there ought to be a greater emphasis on self-determination and self-advocacy skills. Findings from a 2018 report by the National Center for Learning Disabilities, as well as descriptions of a “warrior ethos” by Desgrosseilliers (2014) and Shuford (2009), are used to support a proposal for educators and policymakers to more highly value autonomy, assertiveness and persistence in the characters of Kansas high school completers, whom the author refers to as “College and Career Ready Warriors.” [Note: This paper is based on a presentation by Robb Scott at the 2018 Strategies for Educational Improvement Summer Conference in Lawrence, Kansas.]

In the year 2014, the Kansas State Board of Education issued instructions that every Kansas student, starting in 8th grade, will have an individualized plan to prepare for their transition from secondary school to college, vocational training, and/or employment (Reed, 2014). This mandate for the IPS in Kansas was a firm echo of the transition planning first mandated for youth with special needs in IDEA 1990 (Johnson & Sharpe, 2000; Williams & O’Leary, 2000).

Transition planning ideally begins as early as possible in a child’s life (Cronin & Patton, 1993); accordingly, to support the IPS and College and Career Readiness initiatives, KSDE has developed a sequence of career-related curriculum guidelines from kindergarten through 12th grade, connected by an emphasis on seven career fields, and their related clusters and pathways to specific jobs (KSDE, 2017). In special education in Kansas, the individualized education planning process traditionally has shifted its emphasis when a student turns 14, at which point every meeting of the IEP team must address transition planning for that student, starting with his or her vision, hopes, goals, and dreams (Kansas State Department of Education, 2009)

Morningstar et al. (2017) look at Kansas and other states that are implementing College and Career Ready curricula for all students. These researchers break College and Career Ready down into a framework of six domains: academic engagement; critical thinking; mindsets; interpersonal engagement; learning processes; and transition competencies (Morningstar et al, 2017, p. 84). Next, Morningstar et al. (2018) have considered College and Career Ready standards in the context of the three tiers of MTSS. They describe three tiers for each of the six College and Career Readiness domains. Below is their description of the mindsets domain as it would appear if overlaid on the three tiers of MTSS.

Yet there is a conceptual problem with trying to maintain the MTSS framework, since the IPS initiative has created a hyper-inclusive mandate, treating each student as if he or she were on an IEP preparing for transition from high school to college or the workplace. In a sense, the same factors driving “Kansans CAN” and College and Career Ready curricula may be bearing down on—rather than lifting up or supporting— the individual student with or without disabilities.

The Role of Self-Determination in Transition Planning

Special educators are trained to develop a great sensitivity to the individual needs of learners, and this goes far beyond simply “caring” about our students. There is nothing paternalistic about the systematic approach a true special education professional takes when supporting the transition planning process for students with special needs. Self-determination is central to a successful transition planning process (Bambara et al., 2007; Geenen et al., 2003; Klingner et al., 2007; Portley, 2009; Shogren et al., 2015; Trainor et al., 2008). Education theorists including Dewey (1916), Freire (1970), hooks (1994), Rogers & Frieberg (1994), and Greene (1995) all speak to the compelling difference it makes when the impetus for change, learning and growth comes from within the individual himself or herself, not imposed by an external force or system.

In 2018, the National Center for Learning Disabilities conducted online discussions with special educators, personalized learning specialists, teachers, parents, students, and education advocates on ways to incorporate self-determination and self-advocacy skills into how students are taught in schools today, with an emphasis on preparing students for what is referred to in Kansas as College and Career Readiness. In their report on the results of their study, “Agents of their own success: Self-advocacy skills and self-determination for students with disabilities in the era of personalized learning” (2018), the NCLD defines self-determination as “an empowered state in which individuals take charge of their lives, make choices in their self-interest and freely pursue their goals” (p. 2).

The present author wishes for the reader to agree with a single premise: concepts, skills, and best practices from 30 years of development of transition planning in the field of special education are relevant to the goals of “Kansans CAN,” Individual Plans of Study, and the College and Career Ready curriculum now rolling out across the state. The key themes of the NCLD in its report on empowering America’s children and youth are in concert with the vision of the education leaders of the State of Kansas today, in the context of Kansans CAN and the exciting new Mercury, Gemini I and II, Apollo, and Apollo II school and district restructuring initiatives.

In an analysis of data from surveys as well as interviews and virtual focus groups, in research funded in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the NCLD discerned three policy and action themes to “ensure that self-advocacy skills and self-determination are woven into learning for all students and supported by a full range of engaged stakeholders” (p. 3).

1. Make self-advocacy skills and self-determination critical

priorities in personalized learning systems.

2. Ensure that learning opportunities are designed to maximize

engagement of all students, regardless of disability.

3. Provide students tangible opportunities to practice self-advocacy

skills and self-determination.

(NCLD, 2018, p. 3)

According to research in the NCLD report, “few individuals automatically develop the level of self-awareness and mental skills to fully understand their strengths and weaknesses, set ambitious and practical short- and long-term goals, or stand up for themselves and communicate their needs to authority figures.” Notwithstanding, the NCLD report warns, “these skills are needed for future success in higher education, employment, and civic life.”

Promoting Self-Advocacy for All Kansas Students

Changing mindsets and systematic sources of oppression is not a new concept for special educators. Participation and engagement of students and all families can be enhanced by strategies that sensitive special educators and counselors already use to support children and youth so that they have access to experiences that develop self-determination and self-advocacy skills. Laurie Powers, in a 2017 article, argues that “feeling understood and respected is affirmed through seeing one’s perspectives and expertise reflected in decisions.” As one example of how to give community members with severe disabilities access to such experiences, Powers describes “the five finger method” (attributed to Nicolaidis et al., 2011).

That example of the five finger method and how it supports access, communication, and participation for individuals with severe disabilities, ought to inspire teachers, counselors, and mentors to discover innovative ways to empower all students in a general education college and career prep context, giving each student many chances to develop the awareness and skills upon which self-determination and autonomy are built. School principals, school counselors, classroom teachers, and any other adult staff member in the school who participates in guiding middle school or high school students through their individual plan of study process will understand the responsibility of being an advocate for students and engaging them and their families in an empowerment process that changes lives.

Initial Steps for Adding Self-Determination to the Curriculum

There already are places in the current College and Career Ready curriculum to consider incorporating self-determination and self-advocacy instruction. For example, at the seventh and eighth grades, it is important to realize that “American Careers” is not just a magazine, but a whole set of resources with topics and issues where adults can begin helping the student make connections to self-determination perspectives. At ninth grade, job shadowing and discussions about future plans with the counselor and the student’s family are also potential opportunities for opening situations that allow students to practice making choices and develop self-advocacy skills. At tenth grade, if the school curriculum were linked in a conscientious way to the student’s first conversations at the workforce development center, this would provide another perfect opportunity for experiencing what it means to develop a personal and career vision. In 11th grade, self-advocacy skills can be reinforced through the experience of engaging with one’s local community and developing service-learning projects. Another idea for 12th graders, as they prepare for the transition to post-secondary settings, is for them to take on mentoring roles with elementary and middle school students who are at earlier stages of awareness regarding college and career readiness.

Guidance from Special Education: Workplace Skills

There is much from the transition-planning process in special education that applies directly to Kansans CAN and Individual Plans of Study. Vocational training must include social and communication skills to empower the individual to advocate for himself and herself and continue the journey towards self-determination in workplace settings. However, being an adult is not only related to a workplace perspective.

Guidance from Special Education: Daily Living and Lifestyle Skills

Another key aspect of successful adulthood is how a person handles his or her daily life, making lifestyle choices, especially those decisions related to personal freedoms. We can help to empower students by recognizing in them the human need all of us have, to take charge of our lives, imagine a better future, succeed in the workplace, make choices about where we live and with whom, and develop the sense of stability, responsibility, and ownership that comes with experience budgeting and managing our own money. Another important piece of a fulfilling life as an adult in society is making healthy choices and understanding the habits that contribute to our personal safety, while at the same time feeding our souls with art, music, and entertainment. These are called leisure activities, and a person with these skill sets knows how to find a balance in his or her life between work and play.

Guidance from Special Education: Community Participation and Fellowship Skills

Successful transition to adulthood is also supported by striving towards and achieving social interaction and community participation goals. These crucial aspects have to do with building the skills needed to communicate effectively within family relationships, as well as establishing and maintaining friendships.

Developing relationships is going to require self-esteem, a positive self-concept, and above all a high level of self-efficacy, that is, the confidence and belief we can complete what we have started. Through community participation, students have the opportunity to develop this vital sense of self-efficacy. It is encouraging to see service-learning and community involvement emphasized in the College and Career Ready curriculum as already practiced in Kansas schools. Through working on behalf of others in our communities, we also improve our understanding of what it means to campaign for community-improvement causes or to represent ourselves and others in an advocacy role.

The Present Day Image of a Kansas High School Graduate

Empowering a More Assertive High School Graduate

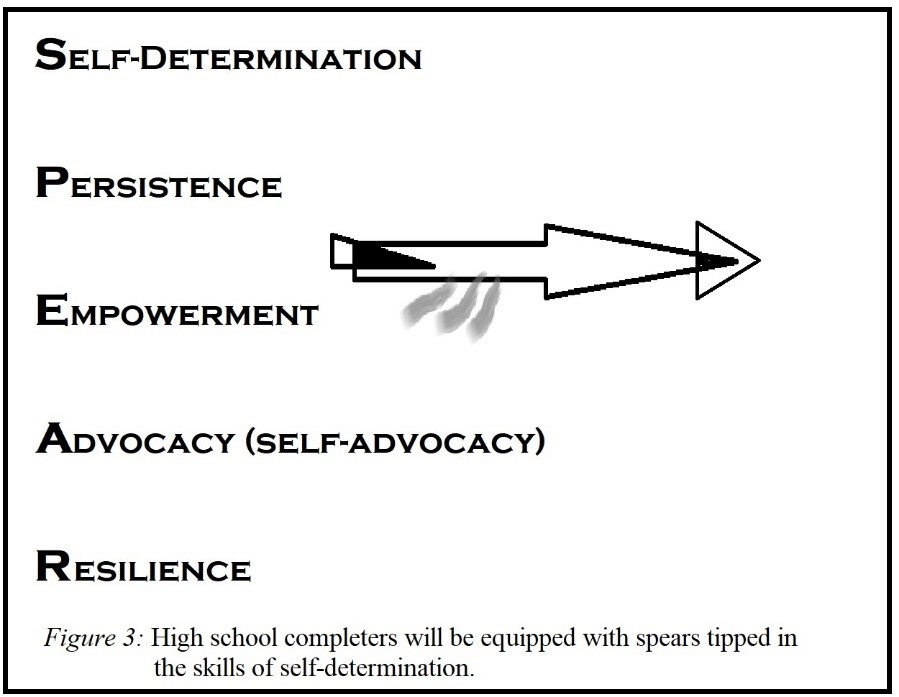

The author of the present paper hopes to stimulate discussion around a more assertive image of future Kansas high school completers, as “warriors” with their feet firmly on the ground yet with “Ad Astra Per Aspera” imprinted in their souls, educated not only to fit into the current business and social context, but also girded with self-advocacy skills to improve their lives and having developed both a strong sense of self-determination and a warrior ethos that compels these future Amelia Earhardts, Dwight Eisenhowers, Carry Nations, and Oliver Browns to stand up for themselves and grapple with challenges none of us can predict that the state of Kansas may face in the future. In this case, the word “warrior” is used in a special sense, supported by the second definition of the word in the 2018 Unabridged Random House Dictionary: “a person who shows or has shown great vigor, courage, or aggressiveness, as in politics or athletics.”

The Kansas high school graduate of the future would share many of the same traits and qualities described in a 2014 Marine Corps Gazette article on the warrior ethos by Todd Desgrosseilliers. In his article, the author talks to the “expeditionary mindset” of the ideal warrior, “that associates personal character, experience, and training intrinsically with personal education, imagination, and values…” He goes further to extol leaders who “weave mental agility, resilience, self-reliance, and ethics into our daily activities” (Desgrosseilliers, 2014).

Desgrosseilliers is the President and Chief Executive Officer for Project Healing Waters Fly Fishing, Inc. – a nationwide nonprofit organization that provides rehabilitative fly fishing programs for disabled active duty personnel and for disabled veterans. Non-veteran and veteran readers will be awestricken by Desgrosseilliers’ statement that “it is possible for what we do in this life to echo through eternity” (2014). What could constitute any higher of a moral imperative for Kansas schools to strive to embody in an invigorated College and Career Ready curriculum with a renewed emphasis on self-determination and a warrior ethos?

Equipping the Kansas College and Career Ready Warrior

In a 2009 article “Re-Education for the 21st-Century Warrior,” Jacob Shuford, then President of the U.S. Naval War College, writes: “Experience yields great quantities of personally relevant detail of transient value, but buried in that detail are kernels of knowledge that endure long after the drifts of experience melt away” (2009). Shuford follows those words with an unattributed quotation: “Education is what’s left when you have forgotten all the facts.”

Fellow Kansans are asked to imagine a future Kansas high school graduate, or College and Career Ready Warrior, emerging from 12th grade armed with a figurative spear composed of what shall still remain years later, when he or she has long since forgotten many details we may have thought to be most relevant, and our names and faces have faded from our students’ memories.

References

Bambara, L.S., Wilson, B.A., McKenzie, M. (2007). Transition and quality of Life. In Odom, S.L., Horner, R.H., Snell, M.E., Blacher, J. (Eds.), Handbook of developmental disabilities (pp. 371-389). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Cronin, M.E. & Patton J.R. (1993). Life skills instruction for all students with special needs: A

practical guide for integrating real-life content into the curriculum. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Desgrosseilliers, T.S. (2014). Character and the warrior ethos. Marine Corps Gazette, 98(9), 62-64. https://search.proquest.com/marinecorps/docview/1560336937?accountid=48498

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy in Education. New York: Macmillan.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Ramos, M.B., Trans.). New York, N.Y.: Herder and Herder.

Geenen, S., Powers, L.E., Lopez-Vasquez, A., & Bersani, H. (2003). Understanding and promoting the transition of minority adolescents. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 26(1), 27-46.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. London: Routledge.

Johnson, D.R. & Sharpe, M.N. (2000). Analysis of local education agency efforts to implement the transition services requirements of IDEA of 1990. In Johnson, D.R. & Emanuel, E.J. (Eds.), Issues influencing the future of transition programs and services in the United States: A collection of articles by leading researchers in secondary special education and

transition services for students with disabilities (31-48). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Kansas State Department of Education. (2009). The transition-focused IEP process.

Kansas State Department of Education. (2017). Career cluster guidance handbook: Kansas Career Cluster Pathway design models.

Klingner, J.K., Blanchett, W.J., & Harry, B. (2007). Race, culture, and developmental disabilities. In Odom, S.L., Horner, R.H., Snell, M.E., Blacher, J. (Eds.), Handbook of developmental disabilities (371-389). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Morningstar, M.E., Lombardi, A., Fowler, C.H., Test, D.W. (2017). A college and career readiness framework for secondary students with disabilities. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 40 (2), 79-91. doi: 10.1177/2165143415589926

Morningstar, M.E., Lombardi, A., Test, D. (2018). Including college and career readiness within a multitiered systems of support framework. AERA Open, 4(1), 1-11.

National Center for Learning Disabilities. (2018). Agents of their own success: Self-advocacy skills and self-determination for students with disabilities in the era of personalized learning. https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Agents-of-Their-Own-Success_Final.pdf

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., McDonald, K, Dern, S., Ashkenazy, E., Boisclair, W.C., Robertson, S, Baggs, A (2011). Collaboration strategies in non-traditional CBPR partnerships: Lessons from an academic-community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 5(2);143-150.

Portley, J. (2009). Educator voices: Perspectives on American Indian student achievement. Paper presented at the national convention of the Council for Exceptional Children, Seattle, WA.

Powers, L.E. (2017). Contributing meaning to research in developmental disabilities: Integrating participatory action and methodological rigor. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 42(1) 42-52. doi: 10.1177/1540796916686564

Reed, K. (2014). Individual plans of study for Kansas students. https://www.ksde.org

Rogers, C.R. & Freiberg, H.J. (1994). Freedom to Learn (3rd Ed). Columbus, OH: Merrill/Macmillan.

Shogren, K.A., Wehmeyer, M.L., Palmer, S.B, Rifenbark, G.G. & Little, T.D. (2015). Relationships between self-determination and postschool outcomes for youth with disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 48 (4), 256-267. doi: 10.1177/0022466913489733

Shuford, J. (2009). Re-education for the 21st-century warrior. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 135(4), 14-19.

Trainor, A.A., Lindstrom, L., Simon-Burroughs, M., Martin, J.E., McCray Sorrells, A. (2008). From marginalized to maximized opportunities for diverse youths with disabilities: A position paper of the Division on Career Development and Transition. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31(1), 56-64.

Williams, J.M. & O'Leary, E. (2000). Transition: What we've learned and where we go from here. In Johnson, D.R. & Emanuel, E.J. (Eds.), Issues influencing the future of transition programs and services in the United States: A collection of articles by leading researchers in secondary special education and transition services for students with disabilities (49-66). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

2020 The Multilingual Adaptive Systems Newsletter

This vision cannot be realized unless students develop the ability

to understand and assert their needs, and the system responds to

them. This means learners have to stand up for themselves and

communicate personal issues that affect their education and ability

to learn. It means, in many cases, the mindset underlying the system

must be transformed.

(NCLD, 2018, p. 3)

Three Action Themes from NCLD

[F]ollowing discussion of an issue and a proposed decision, all [participants]

are invited to show one to five fingers. One finger means I love it. Two

fingers mean I’m not thrilled but I approve it. Three fingers mean I am

not sure and need more information. Four fingers mean I don’t like it,

I won’t approve it, but I can live with it. Five fingers mean I hate this so

much I cannot live with my name being associated with it. Decisions

accompanied by one or two fingers from all participants are approved.

Any time, three, four, or five fingers are shown by even one member,

there is additional discussion to answer questions or consider concerns

and ideas. Following discussion, fingers are shown again. If all participants

show one, two, or four fingers, the decision is approved. If any participant

shows three or five fingers, the decision is not approved and discussion

is re-opened. In addition to facilitating decision making, use of this

approach reassures [all participants] that their perspectives and knowledge

will be considered… (Powers, 2017, p. 46)

A successful Kansas high school graduate has the academic

preparation, cognitive preparation, technical skills, employability

skills and civic engagement to be successful in postsecondary

education, in the attainment of an industry recognized certification

or in the workforce, without the need for remediation.

(KSBE, 2015)

By Robb Scott

editor@multilingualadaptive.net